Sitting with Shame

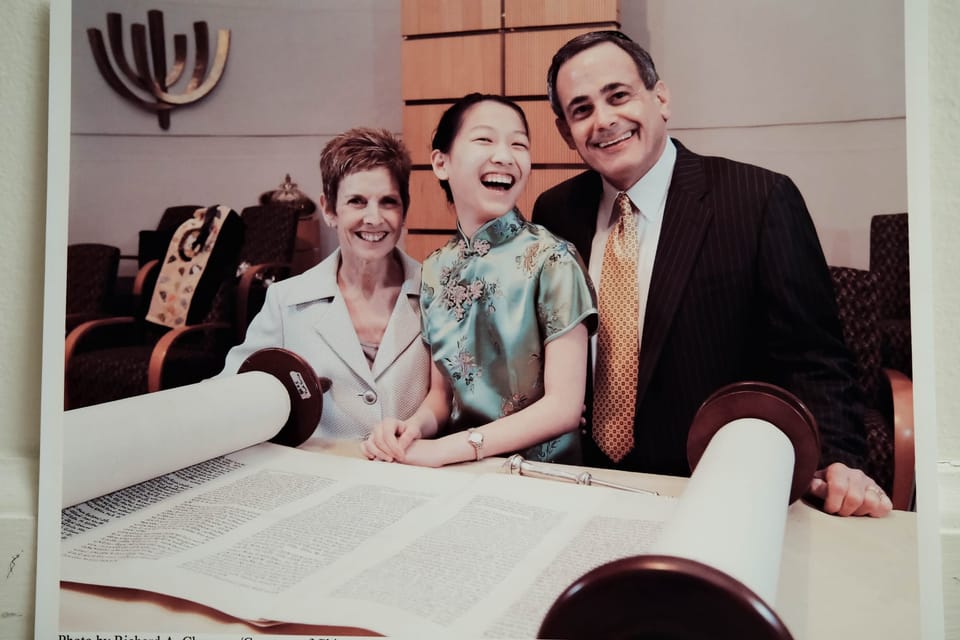

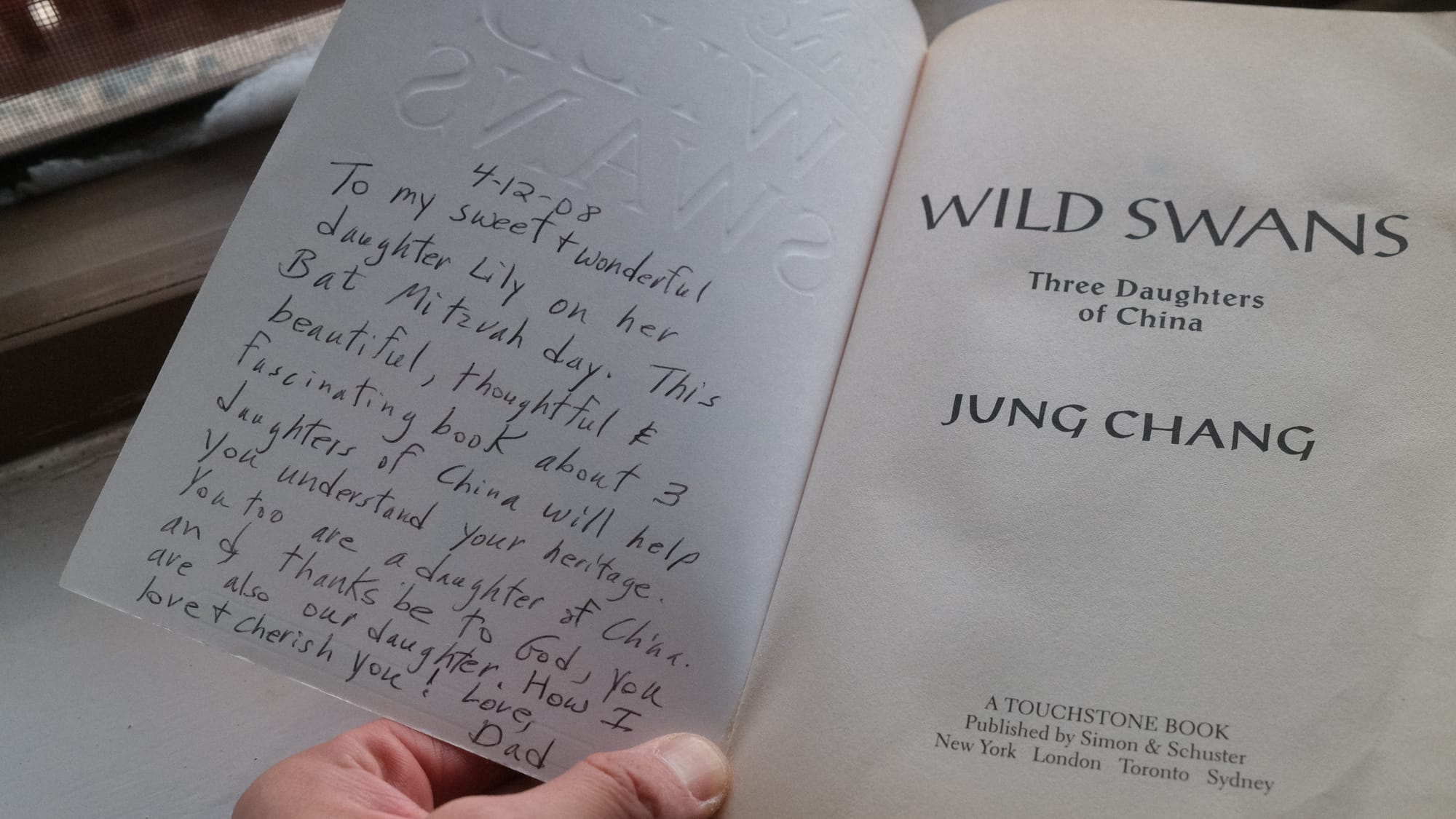

“To my sweet wonderful daughter Lily on her Bat Mitzvah day. This beautiful, thoughtful & fascinating book about 3 daughters of China will help you understand your heritage. You too are a daughter of China and thanks be to God, you are also our daughter. How I love & cherish you! Love, Dad.” (April 12, 2008)

Dad, do you remember writing this? You wrote it behind the cover page of Wild Swans. I remember when you gave it to me. Surely, I was touched. Though as a 12-year-old, I was more overwhelmed by the 500+ page volume. (How in the world would I read this? I still had to finish The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn and write a book report on it!)

Most regretfully, though, I was ashamed.

This shame came shortly after receiving the book, but it wasn't new. No, I'd felt shame my whole life. I'd continue feeling this way to varying degrees for another decade. I was ashamed to be Chinese because it marked me as different. At least with our Judaism, I could keep that sheathed, earnestly drawing it out only when safe. I couldn't hide my almond eyes, olive skin, or flattened nose.

You delivered the book hot on the heels of my pubescent beginnings, which only amplified my shame. I wanted to start dating, but it's hard to feel attractive when people regularly say rude, hurtful things about your appearance in the form of a thinly veiled joke. I chose to assimilate. If I could convince myself I was white, maybe they'd believe it too. And so the social strategizing began. I got out in front of being the butt of the joke by being the joker. My self-deprecating humor knew no bounds. (I cringe when remembering the "jokes" I made in the name of self-preservation.) I wanted to be white. To be white meant to be valued, to be safe.

So, I shelved the book.

From my childhood bookshelf, Wild Swans watched my first relationship and break up. It witnessed how I failed as a friend, and how I rose to the occasion. It saw me cry about my body. It saw me cry about being queer. It saw me cry about being. In those years, Wild Swans collected a healthy layer of dust, unmoved from where 12-year-old me absentmindedly put it. As I packed for college, I packed Wild Swans with the same absentmindedness as I'd placed it. Again, Wild Swans sat untouched, but this time, it was in my desk drawer. The book existed just for me when I missed home.

I read your note throughout my freshman year but didn't ingest the contents until later. Second semester, I enrolled in Asian American Studies 100. Here, I learned, really learned, about Chinese American history. In high school, there were mutterings of the Chinese Exclusion Act in class. However, its teaching went something like this, "Bummer, right? Don't worry: you won't need to know it for the AP test. Let's talk about Grover Cleveland. Did you know he was the only president to serve non-consecutive presidential terms? Now, that might be important." It was in UIUC's AAS 100 course, in tandem with my first gender and women's studies course, that I began to look in the mirror and accept the eyes that stared back.

I finally picked up Wild Swans, not to read your note but to read the book. Dad, if you've been doing the math, this took six years. The world opened up. I was ready to, as you said, start learning about my heritage. I was ready to be Chinese.

The book was a huge gesture. It's among my most prized possessions. At the same time, it wasn't enough. In the decade since picking up Wild Swans, I have learned so much about being adopted. I have learned so much about being Asian American. I have learned so much about myself.

I wish our family had actively learned about Chinese history and culture together, continuously. I wish my Chinese culture had been given as much prominence and solemnity as our Jewish culture. I wish we'd walked through the Chinese American Museum together as I did for the first time last year. I wish someone had prepared me for what it means to be a Chinese woman* surrounded by white people. I wish I'd learned before college that people will not view my body as mine but as theirs, because I am both Chinese and a woman*.

Please don't roll in your grave quite yet, because this is not a censuring of your parenting. This is a mourning of my identity. Blah, blah, blah, we cannot know the unknowable. That said, I dare to think that I would've accepted this part of myself, and other parts, sooner had Chinese culture been more in the forefront of our family's mind. Maybe not but maybe so.

I still haven't finished the book by the way. I can't bring myself to. Doing so is too painful. It's too scary. To finish the book means to take one more step toward realizing your absence. I'm not ready for that, but I'm getting there.

Maybe I'll come by and read it next to your grave this fall.

To my sweet, silly father on this beautiful evening. This beautiful, thoughtful & fascinating book continues to bear witness to my life. Of all the things I've carried, this one is intentional now. Thanks be to god you are my father. How I love and cherish you. Love, Lil. (September 2, 2024)